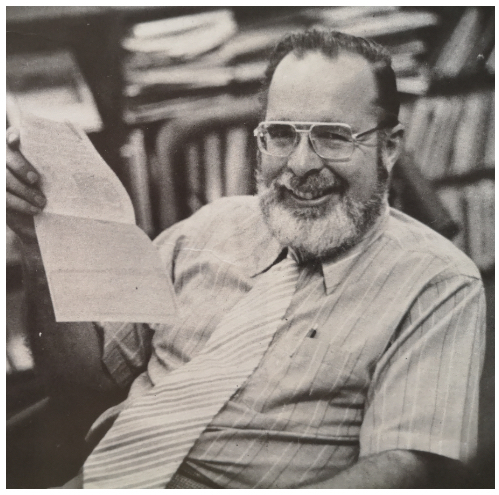

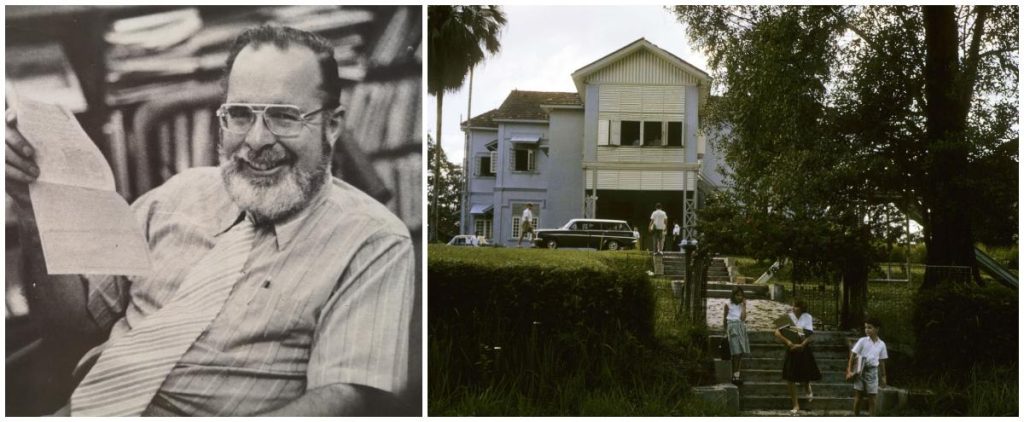

The Gaw surname is synonymous with ISKL – with our first theatre at the Ampang Campus proudly bearing the name of ISKL Head of School, Robert B. Gaw, who led the school for eight years, from 1970 to 1978. This period saw ISKL outgrow its first home at the Istana, and the construction of and move to the new Ampang campus.

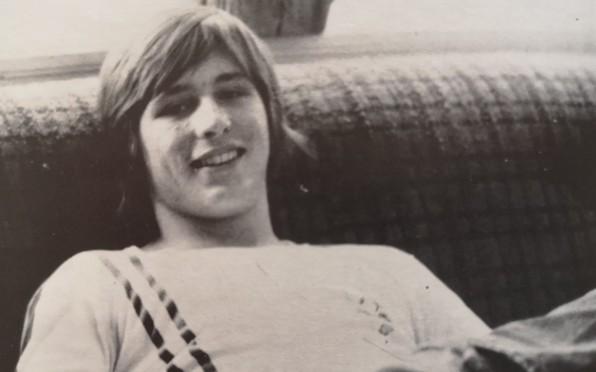

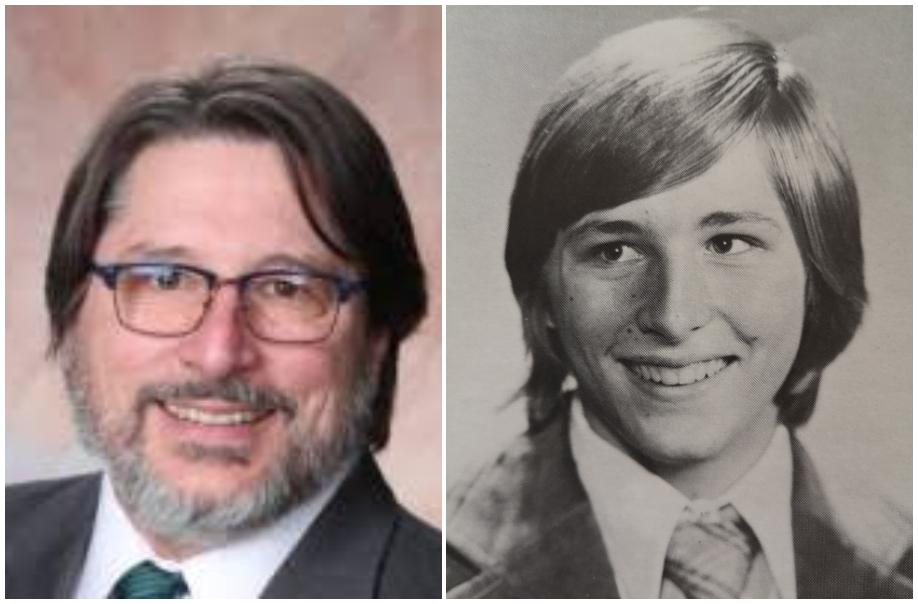

The youngest of the Gaw sons, Kevin, is now Executive Director of the Amica Center for Career Education at Bryant University. He shared his memories of eight adventurous years at ISKL, along with his transition as a Third Culture Kid back to his “passport home”, the USA, with Lynette MacDonald, ISKL Director of Development and Alumni Engagement.

LM: Was ISKL your first international school experience?

KG: ISKL was my first and only international school experience, as it was for my two older brothers, Mike and Jeff. We came to Kuala Lumpur and ISKL in the summer of 1970. We were an adventurous family – always traveling, camping, and backpacking in the U.S. at nearly every chance we’d get. Because my parents were educators, summers were full of such adventures. Going to Malaysia was a new adventure, and we all embraced the trip with excitement. I still remember when I went to the local library in our town in Northern California to learn about Malaysia. Of course, I came home with readings on Malaysian snakes and animals and the jungle; I was 9 years old and I thought I had discovered paradise.

LM: You’re one of three Gaw children who attended ISKL, what do your brothers do now?

KG: Mike owns and operates his own set design and scene construction company in Los Angeles. Appropriately, his company is called Jet Sets and Mike creates some amazing designs! has stayed true to his passion. He has turned into a voracious reader, keeping the family up on titles and topics.

After many years of doing research for new medicines with several pharmaceutical companies, Jeff engaged in a second career, teaching, and he now teaching multiple science courses at the Mary Institute Country Day School. Jeff has always been a scientist at heart (and mathematician and computer whiz) and his ability to teach is something I knew about first-hand (he helped me make it through math and science classes at ISKL!).

LM: Describe the ISKL you remember from your first days in Kuala Lumpur and at the Istana. Was it a major culture shock for your family and for you personally? Was it as “Wild West” as I imagine?

KG: I think for my parents, who started their careers in education by teaching in a 2-room school in a small mining town in southern Nevada, the Istana was another exciting place to work, with its challenges and its beauties. My parents recognized and embraced the wabi-sabi-ness of it all.

As for me – I LOVED the Old School! We really didn’t have cliques in those days and we all engaged with each other – right from the first day. That sort of ethic, of accepting others, is a hallmark of the ISKL experience, especially in the “old days.” We all became friends (and remain so now). I remember long bittersweet drives to the Subang International Airport to see a friend and their family off when they moved away; this ritual, which we kept throughout my time at ISKL, was a testament to our deep friendships and to the relations cycles that help develop the third culture kid identity.

As for the Istana: We would sneak through the fence near the badminton court and swing on some jungle vines, high over the rain gutter (this joyful activity was unfortunately ended by the administration [ahem, my Dad] after a student fell and cracked some ribs in the gutter). We would catch sand lions under the canteen, slide in the mud during rainstorms (and then get into trouble with the administration, ahem, my Dad again), and try to catch snakes and giant (super scary) centipedes along the perimeter. There were “secret” passages (sort of – remember – I was 9 when I got there) to explore and entire worlds to discover. The Istana itself was an architectural wonder for us kids – with its grand staircase inside, multiple entries, “escape routes,” and plenty of hiding places (translate – after school games of kick the can and such). There were also many “risks:” sharp rusty corrugated roofing, falling facades and ceilings, rickety outside stairs and cobras, to name a few. The big soccer field was through a fence, past a broken-down old house, down the hill, and across a small lane. It was on this field under Mr. Daniels’ coaching, we played soccer, rounders, and other sports. After school I flew gliders off the opposite hill with friends and rode bikes down that hill, too, at breakneck speeds.

If you were to listen to the current Zoom calls with classmates from the early years (the Istana years), so many fun stories can be heard. Besides stories of all the typical school kid antics, scrapes, and tall tales, you’d also hear how the unique learning community of ISKL cemented into us so many positive values and perspectives. Intercultural development, appreciation for differences, celebration of others, a sense of kinship with new arrivals, a love for Malaysia, an appreciation for diverse foods (are Malaysians the original Foodies?) and traditions, cross-age and cross-cultural learning, looking up to older students as role models, pride in learning and speaking Bahasa and writing in Jawi, and so much more. We all remember the Old School with such affection.

LM: You mention some brushes with authority; in fact, with your dad! What was it like to be the son of the Principal, then Head of School?

KG: One of the things I remember very clearly was waiting on my Dad after school to go home (this was before I was allowed to ride my bike through Kenny Hills, some 3+ miles). This was in 5th grade – 1970. He’d be in meetings often late and I’d hang out on the front steps of the Istana with a group of friends whose parents were teachers or on the board…and often I was the last kid to go home. This only meant he had a lot of work to get done and those long hours were important. I recall the growing darkness of dusk, the cicadas, the shift in temperature and humidity, and making attempts of doing homework (there was a lot to be distracted by!).

My Dad, the Principal, was very fair about it all. This meant I’d get into trouble, too, and get the same discipline at school as others – and everyone knew it. At home, I’d later meet up with Dad, the family man, and he and my Mom would engage as parents about the issue. So, no special favors from the teachers or staff (much to my disappointment) and he treated me like all my other classmates. This was a relief, actually, as it made it easier to make friends – many of whom are still my friends today.

LM: I’ve been fortunate to recently meet with Joel Wallach who, with his wife Gale Metcalf, was a counsellor brought into ISKL in the mid-1970s when the withdrawal of the US from Vietnam led to not only an influx of refugees to Malaysia, but also an influx of heroin. What was that time like in KL, the ISKL community’s support for refugees, and more generally your experience as a teenager at ISKL?

KG: We all knew about the drugs. I think once a year a DEA agent or an embassy staffer would come to ISKL do some school presentations – usually by assemblies. In those days, it was pot, opium, or heroin. (I guess there was pharmaceuticals, too, but I don’t think any of us knew about those.) And many of us were (appropriately) scared sh*#@%!! by the realities of usage and the very real approach to punishment Malaysian officials would exercise, including the entire family packed up and shipped out within 24 hours (if one was so fortunate), with the father losing his job. That worked for nearly all of us. There were a couple of unfortunate situations, though, and what many of us witnessed reinforced our fears and avoidance.

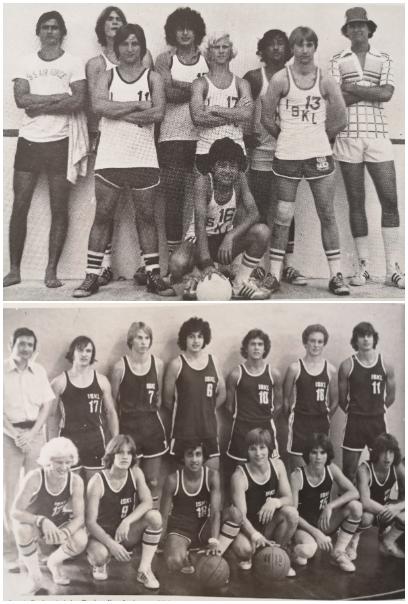

Teenage life was wonderful. My parents really trusted me and, as a result, I did my best to return that trust and respect (I usually did pretty good!). Imagine this: They let me ride my bicycle across KL from Kenny Hills to the Royal Selangor Golf Club at about age 11. I bicycled through the jungle to get to friends’ houses, often through monkey troops who seemed to be lying in wait for me (I was honestly terrified of them). I learned to drive in Malaysia (I delayed my driving test in the US for 3 years because I thought my Malaysian driving “style” may have disqualified me! Lol). I learned to travel in Malaysia, making reservations myself and planning trips. I caught nasty insects that stung, messed with cobras in the backyard, dealt with giant centipedes, chased monitor lizards (or was chased by them), waded in muddy streams during and after rainstorms. I learned how to negotiate and engage with merchants in Bahasa. I learned about the religions and cultures of Malaysia and developed a competency to engage with others with respect, appreciation, and compassion (I eschewed the Ugly American thing). I knew my way around the stalls and local restaurants and had favorite places no one else knew about (or so I thought). I would frequently go downtown just to hang out, walking, exploring, being part of the energy. My parents allowed me to travel by bus or train (even hitchhike) to various destinations while in high school (Singapore, Penang, Pulau, Langkawi, Pulau Perhentian, the East Coast, Fraser’s Hill), either on my own or with a friend. I experienced that forlorn broken heart of teen love – several times, in Malaysia. I had Malaysian pen pals (remember those days?) in Penang and Kota Bharu. I hung out a bit with a Malaysian rock band that played covers. I had a pretty good teenage life, I’d say.

The refugee support efforts were not part of our experience. I think this would have been something important for us to do.

One of the things I am very pleased to see in the ISKL experience now are the various community engagement opportunities.

This is not to say we were not aware of the refugees. We heard about the pirates and refugees, and the terrifying stories of escaping and survival. We monitored Saigon and even “watched” it fall in “real-time” (aka, shortwave radio). We snorkeled the helicopters on Pulau Perhentian, that almost made it to the beach but ran out of fuel just shy, falling into the surf.

Joel and Gail are recalled in the class zoom calls frequently, with fondness. They were sort of like an older, wiser, trusting aunt and uncle. I know they got frustrated with us at times (we were teenagers, after all), but we all look back to the retreats they ran for us, the one-on-one talks, their presence at school – all with fondness.

LM: It must have something to do with longevity, but the Robert B. Gaw Theatre is now affectionately known to many as the RBG. What difference did the move to the Ampang campus, and its new state-of-theart facilities, make for students? As a high schooler, how did it improve your own learning environment?

KG: A group of us had the privilege of helping to move the old school to the new school – mostly the library, I recall. We loaded up lorries with special wood book crates and other boxes, and we would ride in the back of the lorries, to the new school. I remember how we were so excited by and proud of the new school, and with helping with the move.

I loved how the school retained the K-12 environment from the Old School to the Ampang Campus. There were two sides to campus for the classrooms (K-6 and 7-12). The new school was so modern for us! First of all – there was air-conditioning! That, in itself, was a significant change and to be honest, probably helped us with our in-class focus. The library was a big, open space and was bright and modern with the open ceiling and those yellow air conditioning ducts. The canteen was a modern sunken design, with planters. While outside of air conditioning, it was covered and cool – and a great place to do homework during an open period (and close to the food window for nasi lemak or curry puffs – oh yes, these were staples for us!). The theatre, later to be named after my Dad (of which we are all very proud), was something many of us had only seen at the Universiti Malaya (where I remember seeing Duke Ellington!). The space sparked a new level of creative arts for the entire campus (and the ISKL community) and our music and dramatic arts programs improved greatly. The school put on several plays a year and there were musical performances. The theatre (and its associated programs/events) created a new cornerstone to the ISKL community, especially after school, at which many grade levels participated. Which, of course, was the design!

LM: I’m interested to know how your Malaysian international school experience was recognized by universities you applied to in the US. Did you have much explaining to do? What was it like to return to America?

KG: Almost uniformly across my graduating ISKL class, we all experienced the challenges of adjusting to our post-Malaysia “passport homes.” For most of us, it was not easy. Through discussion with other ISKL alumni, spanning all years, my class’ experience was not unique. For me, it took about two years in the States, at college, to feel comfortable. I was also the guy who’d inadvertently let it be known I really didn’t know much about some essential American institutions; hey, I did not grow up in the US! Cases in point: 1) Not understanding or really caring about American football, and asking really naïve questions about the game that brought snickers and deep sighs; and 2) Not understanding how to build a pizza order at the order counter (talk about tension while the employee waited for me) – so I’d ask for the combo/everything just to make it quick and ease the anxiety. (Note: there was only one place to get pizza in KL when I was there and it was a simple, not too appetizing cheese pizza). Trust me, there are more examples!

My ISKL/Malaysia experience was recognized by most of the professors and all of my fellow students at my undergraduate school (UC Santa Cruz, Merrill College). I went to a college that specifically focused on studying developing nations, colonialism, the politics and business of oppression, and such. I studied Mandarin and Bahasa Indonesia. My Majors (double) were Cultural Anthropology and Southeast Asian Studies. I had TCK, international, and domestic (especially those who had studied abroad) friends. The one “trouble” I had was spelling and how to use the English language! It was not a barrier, but I found it interesting that I had adopted British English in much of my spelling while in Malaysia and was constantly corrected on this in college. I also noticed the syntax I’d use was not distinctly “American.” To this day I constantly observe the differences, though I have conformed to US spelling.

Interestingly, it was after my undergraduate college days when I entered my doctoral graduate program, where I had less acceptance of my experiences of growing up in Malaysia and attending ISKL. Graduate-level professors and the grad students, not all but many, saw my upbringing and life experience as very privileged and not that applicable to the theme of our graduate program – which prided itself on multicultural counseling. What they focused on was “American multiculturalism,” not a more internationalized perspective. They seemed to believe I could not have developed cross-cultural competencies. There seemed to be a solid intellectual wall in accepting that a TCK identity could ever exist, and that a white kid who’d grown up outside of the US could have a cultural identity that would be anything other than the prescribed white identity assigned in the US. There was also a belief that a dominant culture person “returning home” could not experience re-entry/reverse culture shock. I had plenty of conversations about this with faculty, citing academic research and experience; needless to say, I had to switch advisors three times (a potentially “dangerous” thing to do in a doctoral program). I was persistent and finished my dissertation, which was, understandably, on the reverse culture shock experiences of overseas-experienced US college students.

LM: You are the Executive Director of the Amica Center for Career Education at Bryant University and you have a long career in psychology and career development. Was it always your dream to work in the education sector?

KG: Education as a profession is deeply embedded in my family. My Dad’s father, an accomplished artist, was an art instructor and later a Dean of Mills College’s art department. My Dad and Mom were educators all of their careers. My uncle Harry (who spent a year in KL on sabbatical from the University of Oregon, while his partner Norm taught in the elementary school at ISKL), helped shape some of my direction, too, through great discussions. My brother Jeff teaches 9th graders (currently). Myself – I started as an ESL teacher with Volunteers in Asia (Indonesia) and then discovered guidance counseling (in which I received my MA in Education/School Counseling), which led me to my doctoral degree in counseling psychology, where I have worked in universities – first in counseling centers then in career centers.

Was it always my dream? I was never drawn to business and I always preferred people, ideas and narratives over making money, balance sheets and inventories. I was drawn to serving others, supporting their success, especially through education; yes, this has always been a theme for me. (Side note: In 6th grade at the Old School, in a “careers” unit, I decided I wanted to be an archeologist, uncovering truths. Hmmm,… not far from counseling, in some ways! Later, in a similar unit in 8th grade, I thought I’d become a pastor, serving others.) I really gravitate toward the idea of working as a team and as a community of colleagues – and this is what educational institutions offer. To be sure, I had no idea how it would develop over the years, but this core theme to my career path has always been there for me and has helped me make good career choices. I deeply appreciate how my parents and mentors supported my process of exploring opportunities without imposing themselves or social expectations.

I often think about the possibility of completing my career back in an international school – a full circle sort of thing, giving back to new cohorts of third-cultured kids and their families.

LM: Tell us about the time you spent in the early 80s with Volunteers in Asia in Indonesia. Were you eager to return to Asia, and how was your Bahasa?

KG: Masih bisa bercakap Bahasa, lah! My Bahasa was pretty good before I left Malaysia and with my time in Indonesia, my Bahasa (which is now a mix of Malay and Indonesian) improved dramatically.

I studied Mandarin my first year in college and later Bahasa Indonesia – hoping to be accepted by Volunteers in Asia so I could get back to Southeast Asia. (I was also an applicant for the Peace Corps and was in the final phases of selection.) In fact, my undergraduate majors were Cultural Anthropology and Southeast Asian Studies – and this was precisely because of my experiences of living and schooling in Malaysia. I very much wanted to return to Southeast Asia and somehow fashion a career there. My proposal to go to Terengganu (a part of Malaysia I loved to visit) to do a deep cultural ethnography (think Clifford Geertz) for my Bachelor’s thesis was turned down – my professors were afraid I wouldn’t come back and finish! So, I wrote my thesis on the expatriate experience.

After college, I went to Indonesia to teach English to future middle school and high school teachers at a Jesuit Teachers Training College. I was serving as a volunteer (Volunteers in Asia) and I was on a volunteer work visa. I deeply enjoyed my experience in Indonesia, where I lived in a small kampung just outside of town. My house had no air conditioning (I had one small fan I moved room-to-room), a well for water, a single burner kerosene stove to boil water, and three light bulbs (one for each small room). I was learning Javanese, made life-long friends, re-discovered the importance of being vulnerable, was awed by the rich cultural history of Java, and was fully immersed in the local, non-expat community. After two years teaching at a Jesuit teacher’s training college in Yogyakarta, I had to return to the US as my volunteer work visa was up with no possibilities for extension. Leaving was bittersweet.

I eventually enrolled in a school counseling master’s degree program, with the aim of returning to Asia, as a school counselor at an international school. After serving as a credentialed school counselor and drug/alcohol interventionist in the Pajaro Valley Unified School District in Watsonville, California, I recognized more training was important – hence my PhD in counseling psychology. This decision directed me to a US-based career as it required a long-term plan that focused on licensure, loan repayment, and a career path that involved university counseling and career services.

Needless to say, I developed and have since maintained strong competencies in serving both international students studying in the US and US nationals going abroad as study abroad students. This was my way of keeping alive my professional TCK identity.

LM: Have you remained close with other Class of ’78 Alumni? After more than 40 years, what keeps you connected?

KG: Yes – we stay connected. Pre-COVID, we had mini-reunions, sometimes annually. We’ve had several “big” reunions, too – and as many as can attend. Because of COVID, Zoom has brought us into more contact and this past summer I hosted multiple class Zoom calls, and more being planned. Several of us also work to find “missing” classmates, using our sleuthing skills gained from organizing the early reunions. I actually maintain for the class a database that goes back to 1970!

What keeps us connected? Our third culture kid identities. Our shared experiences during our formative years. We don’t have to explain much to each other when we tell our stories – we already get the contexts. Our shared post-ISKL experiences in our home countries that highlight how we are a bit different from those who have never been outside their countries/cultures – which unites us. Our continued interests in diversity and the multicultural world.

LM: How is your dad (and mom), and have either of you visited our new Ampang-Hilir campus?

As I recall, my Dad and Mom visited the planned site for the new campus in 2015, at the 50th. Dad saw the blueprints and was very impressed.

My Dad is doing great! He and my Mom live in their Jacks Valley home in Carson City, Nevada – enjoying their high desert views and lifestyle of the Eastern Sierra Nevada (snow is just starting to accumulate in the mountains!). They are pretty active community members – books clubs, music, the Unitarian Universalist Fellowship of Northern Nevada, and such. As always, Dad’s been fully engaged with technology (I remember when he bought the first Mac!) and because of the pandemic, he now Zooms into meetings and regular calls.

I have not had the opportunity to visit in person, though I’d love to! I have watched the videos, the virtual quick tours, and seen photos. The new campus is absolutely amazing – and in fact has a college feel to it.