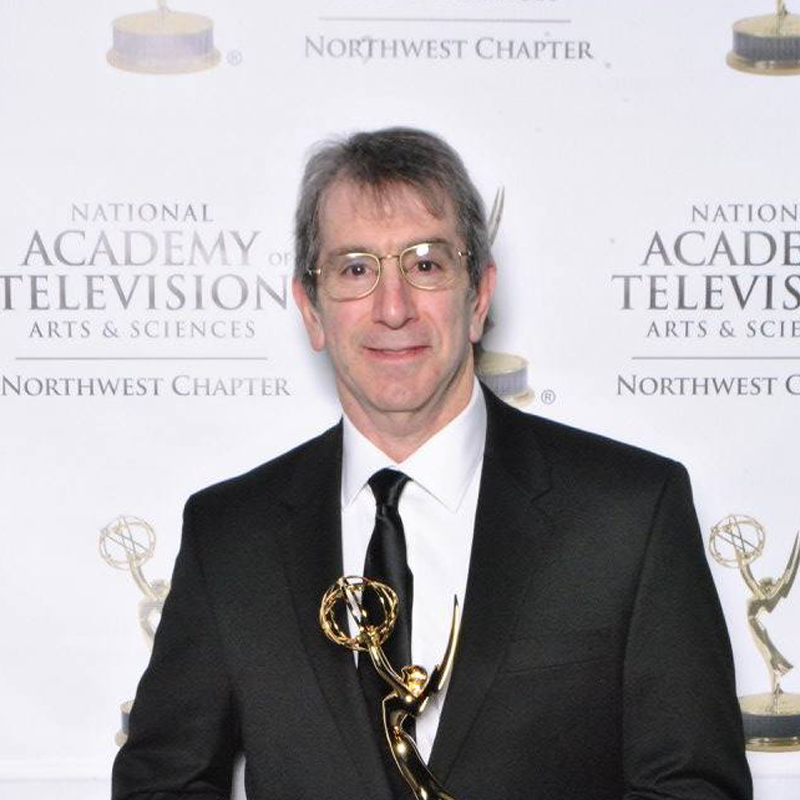

ISKL alumnus, Eric Chudler has taken his passion for neuroscience from the laboratory to the small screen, winning an Emmy award along the way. The son of ISKL’s first Headmaster (Albert Chudler 1968-1970), Eric has also written several books on the workings of the brain, demystifying those “three pounds of tissue in your head”. He is a neuroscientist and research associate professor in the Department of Bioengineering and Executive Director of the Center for Neurotechnology at the University of Washington in Seattle, WA. Eric shared his passion for the brain, career path, and memories of Kuala Lumpur in the 60s with ISKL’s Lynette MacDonald.

LM: How long did you study at ISKL?

I attended ISKL for the two year tenure of my father’s appointment as Headmaster of ISKL. During that time, I was in fifth and sixth grade.

LM: Your father, Albert Chudler, was Headmaster of ISKL from 1968-1970 in ISKL’s formative years. Where had your family come from and what are your memories of ISKL at that time? And KL?

My father was the principal of an elementary school in the Los Angeles area in the 1960s. For personal reasons, he decided that he needed a change and found that a new international school had recently opened in Kuala Lumpur. So, he brought the entire family (my mom, younger brother and system, me) halfway around the world to Malaysia to start a new life.

Kuala Lumpur was a great place to grow up. My parents gave me plenty of freedom and I remember walking everywhere. One particular memory I have is of the large monsoon ditches that often had small fish. I also remember a small shop near our house that sold candy and these very sour, strange tasting dried fruits. And speaking of fruits – the smell of durian is never forgotten.

LM: Where did you go after Kuala Lumpur? What college/s did you attend, and what were your majors?

After living in Kuala Lumpur from 1968 to 1970, my family moved to Los Angeles for one year. My father decided to take another overseas job, this time as Director of the Canadian Academy School in Kobe, Japan. We spent three years in Kobe and then returned to Los Angeles where I finished high school. The University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) was not too far from where we lived, so I decided to go there for college. I did not apply to any other universities at the time. In 1980, I received a Bachelor of Science degree in Psychobiology. Immediately following my graduation from UCLA, I headed north to Seattle where I started graduate school at the University of Washington. I received a M.S. (1983) and Ph.D. (1985) in Psychology.

LM: You are now a university professor, author and TV presenter…but how did your career evolve?

When I started college at UCLA, I did not know what I wanted to study. In fact, I was an “undeclared major” for my first two years. In my third year, I took an introductory psychology class from a professor (Dr. John Liebeskind) who studied the brain. I found what Dr. Liebeskind had to say about the brain was fascinating. Dr. Liebeskind invited students to visit his lab and after a brief tour, he asked if I wanted to join his lab as a volunteer researcher. I accepted his offer and worked in his lab and published research papers as an undergraduate until I graduated. After graduate school, I took a postdoctoral fellowship at the National Institutes of Health (National Institute of Dental Research, Bethesda, MD; 1986-1989), an instructor position at Massachusetts General Hospital (Department of Neurosurgery, Boston, MA; 1989-1991) and then a faculty position at the University of Washington (Department of Anesthesiology; and later joint appointment Department of Bioengineering; Seattle, WA; 1991-present).

When my kids were born (daughter in 1990 and son in 1993) and they started school, their teachers often asked parents to drop into their classrooms and talk with the students about their jobs. When I visited my kids’ classrooms, I talked about my work and how the brain works. I always brought activities and games to help teach. Word spread through schools that I would visit classrooms and so other teachers and schools

started to ask me to speak to their students. After years of developing teaching tools to help people learn about the brain, I created the “Neuroscience for Kids” website so teachers, parents and students could access the materials from anywhere in the world. Later I thought that books and TV would be other good ways to make neuroscience accessible to everyone.

LM: In 2017 you won an Emmy for your TV show, BrainWorks. How challenging is it to take the leap from scientist to science communicator?

The skills used by scientists and science communicators are different. Scientists most often relay their research results to their peers who are already familiar with a particular topic. Therefore, scientists may use language that makes it difficult for non-experts to understand. Having been around educators for so many years (my dad was a teacher before he was a school administrator and my mom was an elementary school teacher), I realized how important it was to communicate ideas clearly so everyone understands. There are methods and techniques to help people communicate more clearly, but I think the most important activity for people who want to connect with others is to practice.

LM: When you’re writing or working on the TV show, how do you ensure your work is accessible to the general public? That’s such a skill – is there a method you use?

The BrainWorks TV show is intended for kids in middle school who are interested in science. So, it is important to have kids of this age not only on the show, but also to provide feedback about the content of the show. I also get feedback from teachers and parents who watch the programs with their students and children.

LM: How do you decide the topics of your books, and your TV series episodes? Do they come from everyday conversations?

The motivating factors for deciding on topics for my books and TV shows are different. For the books, I do talk to people about what interests them the most. People often ask me questions about things that they have seen or read in the media and would like to know if the information is correct. I hope that the material in some of my books will help readers become more critical consumers of what they see and hear. For the TV shows, the topics are sometimes influenced by the source of funding.

LM: What’s the most amazing thing about the brain (for you)?

Your three-pound brain is composed of approximately 86 billion nerve cells (neurons) that guide everything that you do: movement, perception, memory, emotion and much more. But perhaps most amazing is that those three pounds of tissue in your head somehow tell you that “you are you.” In other words, the brain is responsible for our conscious experiences.

LM: Did you know when you were a student at ISKL that you wanted to pursue neuroscience?

When I was at ISKL, I was only 11-12 years old and I really did not have any idea what I wanted to study. To be honest, I was more interested in just being outside (and swimming in the pool at the Royal Selangor Golf Club).

LM: Did you have any particular teacher who was influential in encouraging/supporting you to enter this field?

Perhaps the most influential teacher I had was one of my high school biology teachers. I took an elective class where students could pursue any interest that they had in marine biology. In fact, after that class I thought that I would become a marine biologist and took many biology classes while I was an undergraduate at UCLA. Although I decided to pursue neuroscience, the experience in that high school biology class kindled my love of science.

LM: How do you think your time as an expat kid, both in KL and Japan, influence the person you have become, your outlook and choices?

Living overseas has reinforced my understanding that the world is full of people with ideas that are different from my own, who speak languages I do not comprehend and who have customs that are not like mine. Such differences should be respected, valued and appreciated. I wish everyone had the opportunity to experience life in another country.

LM: What advice would you give students interested in a career in science now?

Science and technology are advancing faster now than ever before. Although we know a tremendous amount about the world around us, there is still so much more to learn. I suggest that students approach a career (in science or any other discipline) as a puzzle that needs to be put together. Find the pieces that are needed to complete the puzzle, make a plan to see how the pieces fit together, and then take the necessary time to make the puzzle whole.

LM: What do you wish you had known when you were starting out that you know now?

When I first got started, I did not realize how important personal contacts and recommendations would be to getting to the next step. A network of advisors and mentors who can provide a good word for a person is often critical to landing a job or scholarship.